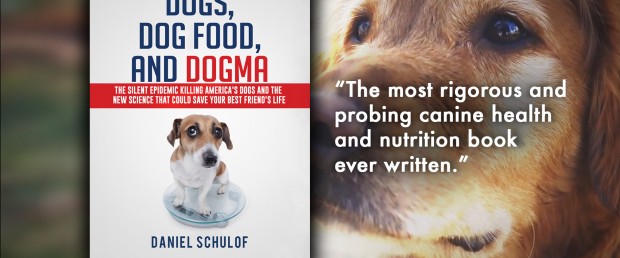

What follows is another excerpt from my forthcoming book Dogs, Dog Food, and Dogma (available for pre-order here). In it, I recount my experiences at the SuperZoo convention, one of the world’s largest pet products expos. This excerpt serves as something of an introduction to the dog food business, a subject that I cover in greater detail in the chapters that follow this one.

Now, two quick things before we get started:

1) If you’re interested, you can enter for a chance to win an autographed copy of the book here. But act quick, because the contest will close tomorrow afternoon.

2) I’ve put together a short video trailer for the book. If you like what you see (or what you read!) please feel free to share it with your social media tribe. To encourage you to flex your reading muscles a bit, I’ve placed it way down at the bottom of the post.

Enjoy!

DOGS OF THE LAS VEGAS DESERT:

THE LAS VEGAS STRIP in the summertime is no place for a dog. With temperatures often rising above 110 degrees, the heat on the street is crippling. The sun is ever-present and burns blindingly bright. It’s enough to cook a man right through the best efforts of his highly-evolved system of pores and sweat glands. Dogs, whose self-cooling strategies are more limited than our own, and generally amount to some combination of panting, hiding in the shade, and finding a cool body of water, are really pressing their luck when the mercury tops out above 110 degrees. More so than even us, they’re better off just staying away.

The economic super-machine of Las Vegas is, of course, designed to capitalize on the oppressive summer sun. When the desert heat is at its worst, the allure of the mega-casinos is at its strongest, their doors flung open to bathe sweat-dampened pedestrians with waves of machine-cooled air and promises of luxury, excitement, and sex. But, unlike their human counterparts, urged as they are to escape the midday swelter getting rich inside a cool casino or sipping an expensive frozen drink, dogs are generally unwelcome inside the Strip’s finer establishments. Unburdened by hopes and dreams and, in many cases, with neither the hygiene nor the manners needed to thrive in polite human society, they’re not particularly beneficial to a casino’s bottom line. Alas, in Sin City there just isn’t much money to be made off of a lowly mutt.

Or so you might think. And yet, on an epically hot day in mid-July there are tens—perhaps hundreds—of thousands of dogs gathered together at the Mandalay Bay Convention Center at the south end of the Strip. At first glance, they seem to form a representative sample of the American canine population. They certainly reflect all the physical diversity for which the domestic dog is renowned: titanic St. Bernards and English Mastiffs lumber along next to wholesome, square-shouldered Labrador Retrievers while dainty, carefully coifed Malteses sit nearby, perched like child emperors on embroidered throw pillows.

But in other ways this group of dogs is special. For one, they’re all a little too pretty. The black polka dots on the Dalmatians are spaced a bit too perfectly from each other and stand out in unrealistically stunning relief against their bleach-white coats. All the dogs seem to be wearing the same handsome facial expression too—a playful, confident grin, corners of the mouth drawn back, tongue lolling out between nicely aligned teeth. Even the bulldogs, a group of animals that have literally been engineered to be ugly, don’t look so bad. Like a television actress playing a pre-transformation ugly duckling, each one seems just a makeover away from becoming a prom queen.

There aren’t many representatives of the so-called “aggressive” breeds either, despite their popularity throughout the broader American canine population. Very few German Shepherds. Even fewer Rottweilers. No Pit Bulls whatsoever. It’s something I’m particularly quick to note as I wander the convention floor, being a Rottweiler man myself.

But what most distinguishes the thousands of dogs at the Mandalay Bay from the 70 million or so found in living rooms and backyards around the country is the fact that these dogs aren’t living creatures. They aren’t actual dogs at all, just images of dogs.

This goes a long way toward explaining how they can get around the hygiene issue. It also explains why these dogs actually have a role to play in the Las Vegas economy. Because these dogs, these thousands of beautiful, approachable, smiling pooches, are marketing vehicles. They’re making their appearances on product packages and advertising banners, alongside snazzy product names, glowing testimonials, gold seals of approval, and money-back guarantees. They’re in Vegas because they’re part of a larger plan. They’re being used by businesses as part of a concerted effort to sell products and services.

This is the SuperZoo convention, one of the largest and longest-running pet products conventions in the world. There are more than 10,000 attendees walking the floor at this year’s event. For the most part they are buyers, representatives of mammoth international pet retailers as well as smaller regional operations. They look like businesspeople, like middle-managers well-acquainted with the industry convention experience. They wear blazers or skirt suits and tired, road-weary looks. They carry briefcases doubling as overnight bags.

The exhibitors are more of a mixed-bag. The major dog food brands are all here. They’re the household names, the ones that make television commercials and count their annual revenues in billions of dollars. Their exhibition booths are monstrous, sprawling things, with floor-to-ceiling banners, couches and conference tables, and bags of product samples stacked 20 feet high. Each of these outposts is manned by a small army of smiling sales representatives. They are uniformed, with logo-adorned golf shirts tucked into khaki pants. They eagerly distribute glossy sales catalogues to passers-by and engage you in polite, casual conversation when you pause to have a look at their spreads.

The self-styled “specialty” and “premium” dog food manufacturers are also on-hand, with exhibition booths reflecting the curious hybrid status that these unique firms occupy in the marketplace. These are companies that cultivate a staunchly anti-establishment image while enjoying many of the benefits that accrue only to major industry players. Their products are distributed internationally, their advertisements grace some of the country’s largest media platforms, and their private equity investors throw dinner parties for top executives and major distributors at Vegas’s swankiest eateries. Nevertheless, differentiating themselves from the allegedly substandard products and unethical business practices of the major dog food brands is a cornerstone of the specialty dog food business model. But although their exhibition spaces are smaller and more welcoming than those of the mega-brands, they are adorned with cultured accents that belie the “you can trust us, we’re just the little guy” tone of their marketing materials. At one such booth, the display shelves are made out of polished hardwood. At another, a smartly dressed bartender pours glasses of chardonnay while cubes of sharp white cheddar are passed to browsing buyers. After a long day wandering the convention room floor, I find myself feeling grateful for the complimentary refreshments.

Then there are the small manufacturers, the so-called “mom and pops.” These folks occupy small booths on the less expensive real estate toward the back of the convention room floor and display products like deer-antler dog chews and hand-stitched plush toys, stuff produced in small batches close to (and sometimes within one’s) home. Unlike the larger exhibitors, whose booths are manned by models and slickster salesman-types, the mom and pops are usually represented by the company president, an individual often doubling as the business’s founder, accountant, chief financial officer, project manager, and warehouse supervisor. They pass out their product samples and flyers and otherwise try to make their companies look as large and bona fide as they can. Not without good reason, of course—many have dumped their personal savings into their small businesses and have saved all year to splurge thousands of dollars exhibiting at this three-day buyer bacchanal. So while they may not look much like the deep-pocketed mega-brands, they’re just like them in at least one crucial way—they’re here at SuperZoo to sell.

And sell they do. If, like me, you’re a dog owner who is accustomed to being treated first and foremost as a consumer (and not as a re-seller), then the experience of being sold to at SuperZoo might feel strange to you. In these sales pitches, the dog-owning consumer is acknowledged to be a relevant character, but only as a kind of absent third-party, not someone privy to the deal itself. As “they,” not “you.” Rather than telling you why a product will change your life (or your dog’s), salespeople say things like “consumers are really going apeshit over this one” and “the packaging really catches the eye” and “honestly, I’m not sure why they all care about this so much, but they do.”

It’s a different dance than the one performed in a mall or a big-box retailer, where the pitch is inevitably focused on the ways that the product will be useful to you, the end consumer. Here at SuperZoo, the product qualities to which the sales representatives draw your attention aren’t the ones that make the product useful to the end consumer (or his dog), they’re the qualities that make the product useful to a reseller. Because the buyers here at SuperZoo only want to purchase things that they can resell, they need to be persuaded that their customers will perceive the product to be useful. The actual utility of the product is something of an afterthought.

“I don’t need to tell you that the whole ‘grain-free’ thing is getting pretty hot right now,” a spiky-haired young guy in the typical khakis-and-polo uniform says to me with a chuckle.

All this talk about consumer behavior underscores the fact that there are a lot of dollars riding on the buying habits of America’s dog owners. In 2015, Americans spent upwards of $60 billion (roughly the GDP of Kenya) on our canine companions. It is often said that the pet industry is “recession-proof,” that we’ll spend on our dogs and cats regardless of the nature of the economic environment. And, seeing as how we all consider our dogs and cats to be our kids, it’s not hard to understand why. We’ll pay over the odds to buy them the things that we think will make them happy and healthy. We’re all too willing to spoil them with the latest and greatest toys, treats, and other gizmos. We love nothing more than to pamper them with material manifestations of our love.

And don’t the folks at SuperZoo just know it. This whole spectacle—and, indeed, the whole pet products industry—exists only because dog owners feel strong loving emotions for our pets. Succeeding in the world of pet products is basically a matter of convincing dog owners that your products will make their pets uniquely healthy and happy. And from the mega-brands to the mom and pops, everyone at SuperZoo is here making their case. With their emotional television commercials and magazine advertisements, with their handsome canine models and their reassuring product packaging, and with their unending claims that their products are the things dogs both want and need to be as healthy and happy as possible, they’re all just trying to make some kind of connection. To create a narrative, a story that taps into the great emotional undercurrent that binds dogs to their masters.

THE TRAILER:

Leave a Reply